GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

Project Goals and Objectives

The major part of scientific research in archaeological ceramics addresses questions relating to the physicochemical properties of the ceramic body (raw materials used, sizing and mixing of clays, firing temperatures and conditions etc). The motivation for this work has been mainly to answer questions concerning provenance and locality of production.

Even though it is the surface decoration that predominantly encodes cultural specificity much less attention has been paid to the physicochemical properties and even less to the technological processes on which it is based. There are very few cases where this knowledge has been put to the test by actually reproducing the artefacts.

This project builds on the extensive experience of the coordinating partner (THETIS Authentics Ltd) in Researching, Recovering and Reviving the techniques of Classical Attic Pottery (RE3CAP) in order to achieve a reduction of the production cost through the use of innovative technologies while at the same time retaining the material authenticity of the final product. Furthermore the project will enhance Museum visitors’ appreciation of ancient Pottery through multimedia presentations explaining the technological aspects of its production.

The lost secrets of Classical Attic Vases

Rise and fall of a technique

Ancient ceramic art and technology reached its apogee in Athenian workshops during the 6th-5thcenturies BC. During this period the artistic and technological quality of the fired black figure, red figure and plain black glazed vases reached perfection. It was only natural that such perfection had to be witnessed and established by the application of the creator’s signature of which we have several hundreds of examples. We also witness the emergence of schools and workshops which applied signatures as trade marks and guarantees of quality. The incised mark ΝΙΚΟΣΘΕΝΗΣ ΕΠΟΙΗΣΕΝ is the classical precursor of the marks and signatures of the great European workshops of the last few centuries. The products of Athenian workshops were in great demand throughout the Mediterranean markets from Etruria and South Italy, to Carthage, Egypt and the coasts of Anatolia (Asia Minor). The Attic black and red figure vases served as aesthetic and technological reference points for the objects of domestic and decorative usage in very much the same way as the products of the great names of European pottery and glass making (i.e. Wedgwood, Sevres, Limoges, Meissen, Galle, Lalique). The decay of the social and economic fabric of Athens which followed the Peloponnesian war (431-402 BC) marks the beginning of a long period of gradual deterioration of both aesthetic and technological standards, the appearance of lower quality imitations and finally during the Roman period the complete abandonment of the technique. This was the end of the “iron reduction technique”, the most widespread process for decorating ceramics which lasted more than 2500 years. Present day copies which are sold in tourist markets are painted over and bear no relation to the techniques of the Classical period.

The rediscovery

The aesthetic interest in Classical antiquity which followed the Renaissance led to an active search for the lost technique of the so-called ATTIC BLACK GLAZE (Attic BG). In 1752 le Comte de Caylus published a treatise in France where he describes the glaze as “basically ferruginous earth”. Fifteen years later Josiah Wedgwood, after failing to reproduce the glaze he produced the famous ”black basalt” substitutes, decorated in the red-figured style to celebrate the opening of his factory at Etruria (Staffordshire). During the next two centuries chemists, archaeologists and ceramists met with the same difficulties to reproduce the Attic BG devoting articles and treatises to the subject.

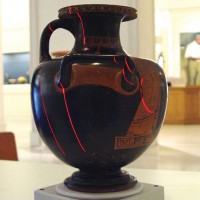

Schumann (1942), Winter (1959) and Hoffman (1962) in Germany as well as Noble (1966) in the USA attempted to overcome similar difficulties by introducing “exotic” additives such as urine, dregs of wine, blood, bone powder, wood or seaweed ashes and modern additives such as Calgon. The definitive answer to the mystery was provided by Aloupi (1993) in Greece in the course of her PhD research on the”Nature and Micromorphology of paint layers in ancient ceramics”. The key to the technique lies in the use of carefully chosen and laboriously processed natural clays in water, followed by a rather complex firing cycle during which the clay based paints acquire their final black or red colour depending on the kiln temperature and atmosphere. The result is a ceramic object, produced without the help of exotic additives, whose colour, texture, chemical composition and microstructure are indistinguishable from the original.

Traditionally, surface decoration has been the domain of the Archaeologist or the Art Historian. For this reason in the case of Attic ceramics of the classical period the museum visitor:

- is not offered the opportunity to appreciate the very advanced level of the underlying technology as witnessed by the excellent state of conservation of the surface decoration and

- is not offered the opportunity to purchase high quality reproductions of decorated ceramic artifacts because of the lack of know-how about the technologies involved and the very high cost of such reproductions.

A notable result is the dominance of the tourist market by low quality acrylic painted ceramics accompanied by a variety of self made so-called “authenticity” certificates.